Over the past few months, inflation – the rate at which the price of goods and services rises – has been heading upwards. Last week, it was announced that US inflation had reached 7.5%. This week, the latest data showed that UK inflation had hit 5.5% in January.*

Given that both the UK and US central banks target long-run inflation of 2%, these figures look dramatically off-course. But why is inflation so high at the moment, and why does this seem to have alarmed financial markets so much?

Why has inflation risen?

Inflation is either surprisingly high or not very high at all, depending entirely on your time horizon. In developed world economies, we have grown used to inflation in the low single digits over the past few years (since around 2014). However, many reading this piece will remember the 1970s, when UK inflation measured in double-digit figures at key points in the decade. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to express concern when a key economic indicator like inflation alters quickly. So, what has changed?

Inflation is the product of a range of factors, including economic activity, commodity and import prices, changes in global supply chains, and shifts in consumer demand. All of these factors have endured a wild ride over the past two years, and will take some time to normalise in the wake of the global pandemic. In many ways, higher inflation can be viewed as a natural by-product of a perfect storm of supply chain squeezes and the release of consumer demand (pent up during population lockdowns), which are distorting price dynamics in the world economy.

Will inflation remain this high forever?

The extent of inflationary pressures in the global economy took investors (including us) by surprise in 2021. Financial markets are notoriously averse to change, so short-term noise in the economic landscape has unnerved them. This has created additional volatility in asset prices, as markets adjust to account for changes in the inflation picture, and – most importantly – their expectations for the likely central bank response (i.e. interest rate hikes).

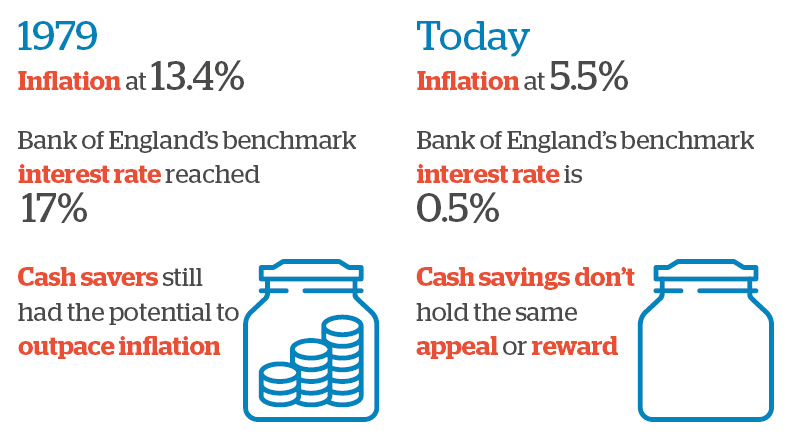

Source: Office for National Statistics and Bank of England.

Figures as at 31 December 1979 and 16 February 2022 respectively.

At the moment, financial markets are also adjusting to a ‘mid-cycle’ phase in the global economic cycle. This kind of environment typically emerges on the heels of the initial burst of economic recovery which follows a recession. It can be a good period for higher risk asset types like shares, but also tends to come hand in hand with greater volatility in asset prices. So far in 2022, we have seen this turbulence playing out in both stock and bond markets.

It’s also worth noting that share prices do tend to be more volatile when inflation is higher, and the types of shares that do well in a high-inflation environment can be quite different to those which perform well when inflation is low. This means that changes in inflation levels can naturally lead to stock market adjustments, as investors attempt to predict where the economy will go next (and, again, how central banks will respond). In this scenario, the relative positions of shares on the leader board move around, and the overall effect is one of market upheaval.

What does higher inflation mean for people with cash savings?

When we speak to our customers about inflation, we often refer to it as the thief that picks your pocket while you look the other way. This is because, through inflation, the money in your pocket becomes worth a little less than it was before, as its real-world purchasing value falls.

Holding your savings in cash therefore virtually always means losing money in real terms, but especially in environments of higher inflation, when the value of cash relative to the cost of goods and services falls more quickly.

Could interest rates rises make cash savings attractive again?

Low interest rates make it cheaper for households and businesses to increase the amount of money they borrow, which can encourage economic activity. This is why central banks lower (or maintain already low) interest rates when the economy needs a boost. However, low interest rates make it even less rewarding to save money, as they allow cash to generate little in the way of financial returns.

Today, interest rate rises are finally beginning, which would normally spell better news for cash savers, but these are moving up very slowly, and from historic lows.

Back in the late 1970s, rising wages and sky-rocketing oil prices led to sharp moves in inflation. As the decade drew to a close, inflation measured 13.4%. However, the Bank of England’s benchmark interest rate was ratcheted up to 17% in 1979, meaning that cash savers still had the potential to outpace inflation, as their cash delivered returns in excess of price rises. Today, with inflation at 5.5%, and the Bank of England’s benchmark interest rate at 0.5%, it’s clear that we are still a very long way off interest rates making cash savings an attractive source of financial returns. Put simply, waiting out the storm in cash doesn’t hold the appeal – or reward – it once did.

What does higher inflation mean for our investment strategies?

Clearly, a period of higher inflation can be challenging for investors who – like us – manage assets against an inflation-linked benchmark. For this reason, we always view performance figures over longer term, aiming to strip out shorter-term noise and market volatility.

Even taking a longer-term view, though, we are acutely aware that inflation-linked targets can be very hard to beat when inflation is high. Nevertheless, we believe that targeting returns in excess of inflation helps to keep us tightly focused on investment solutions that grow the real-world value of our customers’ wealth, rather than sitting back and letting inflation pick their pockets.

No investment comes without risk, and that includes simply holding onto your wealth in cash. However, we continue to believe that investing across a range of carefully selected asset types, with a clear understanding of the potential risks and rewards involved, is the better option for anyone seeking attractive real-world financial returns over the long run.

* When we talk about inflation in the UK and US, we are usually talking about the Consumer Price Index or CPI – a measure of inflation constructed by taking an average price from a mix of goods and services. The data given above comes from the Office for National Statistics (UK) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (US).

Important Information

Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the conduct of investment and protection business, and is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Handelsbanken plc. For further information on our investment services go to wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/important-information. Tax advice which does not contain any investment element is not regulated by the FCA. Professional advice should be taken before any course of action is pursued.

- Find out more about our services by contacting us on 01892 701803 or exploring the rest of our website: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk

- Read about how our investment services are regulated, and other important information: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/important-information

- Learn more about wealth and investment concepts in our Learning Zone: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/learning-zone/

- Understand more about the language and terminology used in the financial services industry and our own publications through our Glossary of Terms: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/glossary-of-terms/

All commentary and data is valid, to the best of our knowledge, at the time of publication. This document is not intended to be a definitive analysis of financial or other markets and does not constitute any recommendation to buy, sell or otherwise trade in any of the investments mentioned. The value of any investment and income from it is not guaranteed and can fall as well as rise, so your capital is at risk.

We manage our investment strategies in accordance with pre-defined risk objectives, which vary depending on the strategy’s risk profile.

Portfolios may include individual investments in structured products, foreign currencies and funds (including funds not regulated by the FCA) which may individually have a relatively high risk profile. The portfolios may specifically include hedge funds, property funds, private equity funds and other funds which may have limited liquidity. Changes in exchange rates between currencies can cause investments of income to go down or up.

This document has been issued by Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management Limited. For Handelsbanken Multi Asset Funds, the Authorised Corporate Director is Handelsbanken ACD Limited, which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management, and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The Registrar and Depositary is The Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, which is authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the FCA. The Investment Manager is Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management Limited, which is authorised and regulated by

the FCA.

Before investing in a Handelsbanken Multi Asset Fund you should read the Key Investor Information Document (KIID) as it contains important information regarding the fund including charges and specific risk warnings. The Prospectus, Key Investor Information Document, current prices and latest report and accounts are available from the following webpage: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/fund-information/fund-information/, or you can request these from Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management Limited or Handelsbanken ACD Limited: 77 Mount Ephraim, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, TN4 8BS or by telephone on

+44 01892 701803.

Registered Head Office: No.1 Kingsway, London WC2B 6AN. Registered in England No: 4132340