In our Investment Outlook 2023, published at the beginning of the year, we said that interest rates and inflation had hogged the limelight in 2022, and our expectation was that this would continue into the early part of 2023. Safe to say, this has happened: central banks have continued to increase interest rates (albeit at a slower pace than last year), and while inflation looks like it has peaked, its descent has not been as rapid as some would have hoped.

In the background, a familiar foe has reappeared: banking sector issues, largely focused in the US, but also claiming a large Swiss institution (Credit Suisse) in Europe. It’s understandable that, for many people, this brings back memories of the 2008 financial crisis. However, it remains our view that this is not another 2008. Today, banks and their balance sheets are very different, with much lower ratios of loans to deposits, and much better quality assets.

For some troubled banks, the recent issues have been down to bad management of the liquidity of their assets (the ease/speed with which these can be bought or sold), or the result of restructuring efforts. Others have been a casualty of the ‘ripple effects’ of a regime change from ultra-low (and even negative) central bank interest rates, towards a more positive and ‘normal’ interest rate environment.

What does this all mean for the global economy?

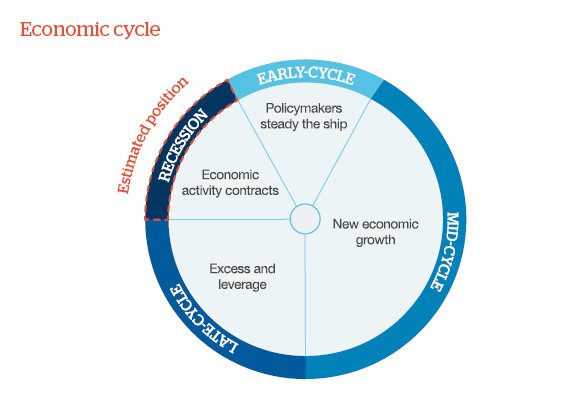

We continue to believe that global growth will slow down before it gets better. As a result, we have moved our global economic cycle position marker from ‘late cycle’ (shown when we included this diagram in our Investment Outlook 2023 at the start of this year) to ‘recession’. As a reminder, the segments of this diagram mark the perpetual fluctuations in the global economy, between periods of relative growth and downturn.

Source: Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management

‘Recession’ is a word that is used too frequently, and often with the wrong connotations. In literal terms, in the UK at least, a recession is merely two consecutive quarters (equating to half a year) of negative economic growth. When we talk about the recession stage of our economic cycle diagram, we are talking about a slowdown in growth over a period of 12 months or more. We do envisage this occurring, but we are talking about a classically-induced period of slower growth, triggered deliberately by policies from the world’s leading central banks, rather than a sudden, deep contraction like those seen in 2008 or 2020.

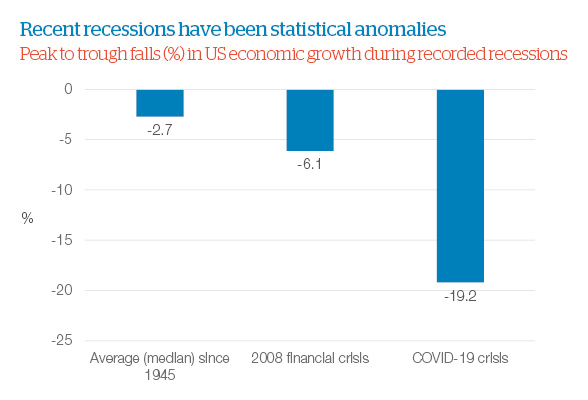

‘Recency bias’ – a tendency to overemphasise the importance of more recent events – can make investors be extremely fearful when economic activity contracts, as it reminds us of the painful recessions of the recent past. However, as the chart below shows, 2008 and 2020’s economic contractions were very outsized, and statistically unusual compared to more traditional downturns.

Source: Bloomberg, Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management

Five reasons we think slower growth is inevitable

1. Stubbornly higher inflation

Inflation may have reached its peak, but it will likely stay elevated relative to central bank targets (2%) for the foreseeable future. And with inflation proving more stubborn than previously envisaged, central banks have been forced to keep their feet firmly pressed on the interest rate pedal this year.

2. Central banks’ history of breaking things

When central banks, particularly the US Federal Reserve Bank (Fed), raise interest rates, history has shown that something usually breaks, culminating in economic slowdown.

3. A global economy sensitive to aggressive rate rises

Since 1955, the average (or median) rise in interest rates during a period of Fed interest rate rises has been around 3% from start to finish. Notwithstanding the ultra-low starting point this time around (0.25%), the Fed has raised interest rates by 5% – significantly more than the historical average. We think it’s very unlikely that the global economy can merely shrug off such an aggressive set of interest rate rises, and is somehow much more immune to rate increases than the past. This suggestion is at odds with history, and not an assumption we are willing to make given the debt levels in today’s global economy (debt is harder to service when interest rates rise).

4. A delayed response in the real economy

It’s probably true that central banks are closer to the end than the beginning of the current set of interest rate hikes, and financial markets do expect developed market rates to be lower 12 months from now. However, the interest rate hikes already in play have not yet fully shown up in the real economy, as central bank policies typically work with a lag. The Fed estimates that it takes 5-6 quarters for a 1% rise in US rates to fully show up in the real economy. If so, then even when the Fed stops raising rates (likely in the coming months) much of 2022’s interest rate rises will not yet be fully reflected in the US economy. This argument can also be applied to other regions, particularly in the developed world, and adds to the risks to growth from here.

5. Fewer loans to companies and consumers

When central banks tighten, the availability of credit to businesses and consumers generally falls. Banks become more discerning regarding who they lend to, as the rising cost of credit becomes punitive to some. As a result we also see the demand for loans fall. Taken together, these factors historically dampen growth in both the domestic and global economy. We are seeing this phenomenon again today. This situation is likely to be exacerbated by some of the issues currently at work in the banking system.

Economic Overview

Click here to view a pdf versionImportant Information

Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the conduct of investment and protection business, and is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Handelsbanken plc. For further information on our investment services go to wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/important-information. Tax advice which does not contain any investment element is not regulated by the FCA. Professional advice should be taken before any course of action is pursued.

- Find out more about our services by contacting us on 01892 701803 or exploring the rest of our website: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk

- Read about how our investment services are regulated, and other important information: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/important-information

- Learn more about wealth and investment concepts in our Learning Zone: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/learning-zone/

- Understand more about the language and terminology used in the financial services industry and our own publications through our Glossary of Terms: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/glossary-of-terms/

All commentary and data is valid, to the best of our knowledge, at the time of publication. This document is not intended to be a definitive analysis of financial or other markets and does not constitute any recommendation to buy, sell or otherwise trade in any of the investments mentioned. The value of any investment and income from it is not guaranteed and can fall as well as rise, so your capital is at risk.

We manage our investment strategies in accordance with pre-defined risk objectives, which vary depending on the strategy’s risk profile.

Portfolios may include individual investments in structured products, foreign currencies and funds (including funds not regulated by the FCA) which may individually have a relatively high risk profile. The portfolios may specifically include hedge funds, property funds, private equity funds and other funds which may have limited liquidity. Changes in exchange rates between currencies can cause investments of income to go down or up.

This document has been issued by Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management Limited. For Handelsbanken Multi Asset Funds, the Authorised Corporate Director is Handelsbanken ACD Limited, which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management, and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The Registrar and Depositary is The Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, which is authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the FCA. The Investment Manager is Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management Limited, which is authorised and regulated by

the FCA.

Before investing in a Handelsbanken Multi Asset Fund you should read the Key Investor Information Document (KIID) as it contains important information regarding the fund including charges and specific risk warnings. The Prospectus, Key Investor Information Document, current prices and latest report and accounts are available from the following webpage: wealthandasset.handelsbanken.co.uk/fund-information/fund-information/, or you can request these from Handelsbanken Wealth & Asset Management Limited or Handelsbanken ACD Limited: 77 Mount Ephraim, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, TN4 8BS or by telephone on

+44 01892 701803.

Registered Head Office: No.1 Kingsway, London WC2B 6AN. Registered in England No: 4132340